On Presenting and Money 201

March 6th, 2015 by PotatoLast week Sandi and I presented Money 201: Planning and Investing at the Toronto Public Library and it was a blast. I think it was one of the best lectures I’ve ever given1. Sandi opened it up with a discussion about goals and direction, making money fit your life, and she did it all with only a few graphical slides. Then I picked up from there to go into investing in a bit more academic way. The room was nearly full, the audience was involved, the energy was good, the questions were great. I hope at some point we’ll be able to do it again.

In brief, my part started with the old fable of the grasshopper and the ant: we know we need to save for the future. Then I took it a step further: with inflation and long lives we need to not just save but to invest. Then a breezy breakdown of what investing is and how it’s kind of scary (discussing risk) and not scary at all (showing how easy passive investing is).

At this point I’m not quite sure what to do with the material — I can leave it alone for now, and if/when we do another seminar then the lucky people who come can see it anew, or I can put up the slides… but that loses a lot without the accompanying talk and discussion. I can also make a video/podcast out of it, but at an hour2 just for my part is a lot to listen to, and a lot of work for me if no one is going to watch it. Let me know in the comments if that’s something you’re interested in (also if you’d prefer to see a video of me standing and gesticulating with my hands as though it were a lecture, or a voice-over on the slides which is cleaner).

Speaking of lots of work, let me now give a behind-the-scenes glimpse at preparing something like this. It basically took about 15 hr of prep time for a 1.5 hr presentation — and I’m still buzzing from the energy of that day so let me go ahead and say that 10:1 ratio of prep time for a great presentation is about right in my experience from preparing other classes and lectures3. Of course, everyone is different: some people can write some bullet points on cue cards in the drive to the talk and be amazing, and my PhD supervisor famously gave other people’s talks cold (zero preparation time), just talking based on what he saw on the slides as they came up and rolling with it. Or check out this guide from TED, which suggests that if anything my 10:1 prep ratio is not practicing enough. IMHO you should always plan at least one real-time practice run, especially if you have a time window to hit — good talks don’t just materialize from being charming and winging it.

First, there was the idea stage: Sandi and I were psyched to do something for financial literacy month 2013; when that plan fell through we took our early discussions and wrote a proposal for the Toronto Public Library and submitted it. Yes, Money 201 actually pre-dates the Value of Simple — we submitted the proposal for it like two years ago now, thinking TPL would go a lot faster. Instead it was over a year before we heard back that there was a branch interested in hosting the seminar, and once they did get back to us they were booking 7 months in advance4.

Anyway, with this actually a go I now had the book in hand, so I set out to try to basically recapitulate it, with some more detail on planning to come from Sandi’s part. Well, as you can imagine, there’s way too much material to cover in that kind of time: I had to create something new that would fit. So I spent about 2 hr putting together a first draft slide deck which outlined a more focused talk, expanding on some parts of the book and ignoring many others. Then I spent about an hour doing a dry run on my own to identify problems with the flow and scope, which led to another 2 hours of slide revisions and rewrites (some of this was digging up a reference for a quote and double-checking some math).

Then because this was a joint presentation I had another 2 hours to discuss it with Sandi so that our parts would mesh together well, and to get her feedback on my early slides. That was followed by another 2 hours or so of revisions and rewrites.

After that I took about 2 hours to practice in front of Wayfare (though the talk was only an hour, there was lots of time to stop and ask questions, discuss what works and doesn’t, to accept criticism, see what’s too detailed, and where things come out of nowhere). I only had about an hour of revisions after that — mostly reordering and cutting slides rather than revising them or writing new ones.

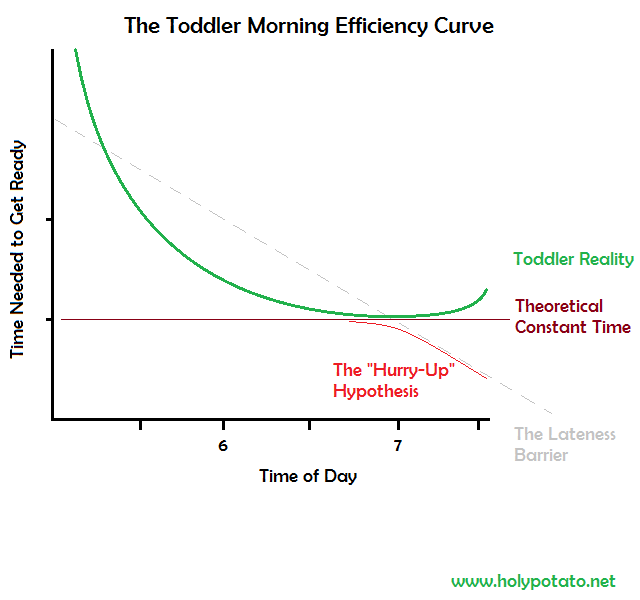

Finally, another hour to practice the “final version” on my own, check the timing and flow — which includes creating a few mental checks, like where the ~1/3 and ~2/3 points are so I’ll know when I might have to hurry up or slow down if I get off my timing at the real thing. That inevitably leads to a last few tweaks of the slides, which with the other prep tasks like copying backups to my cloud drive, a USB stick, making sure I have a laser pointer and bottled water packed, etc., is another hour of prep time.

In all that slide prep I try to think of likely questions and a trick that has carried over from my academia days is to have question slides ready — if I have say 50 slides to present then slide 51 might be my ending “thank you, questions? contact me here:” etc. slide, but then past that I keep slides ready to help answer questions. Many of the extra slides I had to cut back on for time are kept there because I don’t like deleting things, as are a few slides I made just to be ready for questions. Even if I don’t have to bring them up to answer a question, that kind of advanced thinking of likely questions (and their answers) really helps the Q&A part go more smoothly.

A financial literacy event like this can feel really good to do — lots of happy people in that audience who walked away knowing more and feeling better about their money and how it intertwined with that future, which is affirming for us as presenters. But make no mistake that it’s a much bigger time commitment than just the hour or two spent up on stage.

1. and if I may toot my own horn, that is indeed saying something.

2. and to toot horns again, our timing was great — few people appreciate coming in on-time for a 1.5 hr lecture, but it is important and requires work and practice to nail it.

3. for my PhD defence it was naturally more, closer to 200:1 (and that’s not including data analysis tasks like making graphs — just presentation prep). I had a very indulgent and supportive lab group who critiqued me through three full-length practice runs.

4. so using that as a guide, if you’re interested in seeing another Money 201/new title TBD with Sandi and/or me, it likely won’t be for another year or more, at least at TPL.

Questrade: ETFs are free to trade, and if you sign up with my link you'll get $50 cash back (must fund your account with at least $250 within 90 days).

Questrade: ETFs are free to trade, and if you sign up with my link you'll get $50 cash back (must fund your account with at least $250 within 90 days).  Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including sending you an email reminder when new cash arrives and is ready to be invested.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including sending you an email reminder when new cash arrives and is ready to be invested.