TLDR: The Rule of 30: A Better Way to Save for Retirement is focused on a singular question: “how much should I save for retirement?” This one is central to personal finance, and worth some discussion. Vettesse approaches it in a neat way, looking for how to smooth your consumption over your lifetime. I love that this book exists and takes this seemingly simple question seriously. However, I have some quibbles with the titular rule of thumb, largely because it doesn’t work for my particular situation, and he didn’t lay out any guidelines for when the rule breaks (not even “if you’re a sentient tuber, this rule may not be for you”). The discussion to get to the rule-of-thumb and some of the considerations are good and important to read, but I didn’t personally care for the book’s narrative format.

I don’t like finance books that try to teach personal finance things through a narrative, it’s just a pet peeve. I know, the Wealthy Barber is one of the most successful books ever, but not everyone writes as well as Dave Chilton. Well, it’s not just a pet peeve, it really doesn’t work in some ways. I felt that way with The Rule of 30: A Better Way to Save for Retirement — there was a lot to like with the book, but the filler really detracted from the experience.

“You mean we won’t be finishing today?” asked Megan, looking a little disappointed.

“I’m afraid this process we’ve embarked on will take a while, if you want to do it right. This seems as good a place to break as any.”

“Of course,” Megan responded, “but you should know we’re not going to be able to sleep until we know what happens with our $2.7 million. Are you free tomorrow?”

“I think so,” Jim replied. “I’ll check my calendar at home and text you with a time. Next time we’ll meet a my place…”

This is not a rich and engrossing story that happens to also teach a lesson, it’s a narrative device that makes the book about 3 times as long as it needed to be.

“But Potato, the book is only 190 pages long as it is. How else am I supposed to pad it out?” Fred Jim asked the freelance substantive editor and subject-matter expert in an email.

“Jim, I don’t know what to tell you. To say that the characters are one-dimensional is to besmirch the character development of lines,” Potato said, sharing a harsh but necessary truth. “The book requires significant re-writes before it will be engaging. Plus you don’t spend nearly as much time as you could discussing the titular rule itself, or it’s shortcomings.”

Jim, the findependent former actuary, thought about that for a bit. It was a bitter pill to swallow, but it was an important lesson from an independent voice in the field — and not something his publisher’s copyeditor was telling him.

The next day, he invited Potato over to discuss it more. He started setting up lawn chairs in the back yard for a discussion, oblivious to the frigid December air. “Potato, I’ve given a lot of thought about what you said about my book needing to be padded out.” He waved a new manuscript in front of his face. “What if we add a bunch of unnecessary actions and establishing text too?”

“You’re not hearing me, that’s slowing the reading down without making it more interesting,” Potato said, direct and to the point. “If the characters are just saying the things you want the book the say, there’s not much point in having the characters there.”

“Hmm, you’ve given me a lot to think about here, my good Doctor Spud. May I call you Stormageddon, Editor Extraordinaire?” Jim said, gathering his lawnchairs back up.

“Please don’t, that’s just a cheap callback to a previous post. I do have one final piece of advice for you before you go: read the dialogue out loud and see how it sounds. Does it flow naturally like human speech, or are you just throwing quotation marks around an essay?”

The next day, Jim knocked on Potato’s door at the crack of noon. Potato stumbled out of bed to get the door, threw on an N95, and answered the door otherwise in his PJs. “What?!” he demanded.

“I did that thing you suggested and read the dialogue out loud. It sounded exactly like how three actuaries talk to each other,” Jim proudly announced.

“Only one of the characters is an actuary, though.” Potato pointed out, rubbing his forehead. “The other two are supposed to be normies.”

“The dialogue is fine,” Jim insisted. “Just fine.”

“Ok, well how long did each scene, which was supposedly stretching on so long that the characters had to break to pick the discussion up later, seem to take?”

“Exactly two minutes,” Jim proudly stated.

“Yes, it’s like they’re talking between commercial breaks while watching old-school TV. People have Netflix now, Jim, and anyway, there was never a TV on in the background.”

“My media manager says I have to convey information in two minute chunks so I can be invited back on BNN or get a YouTube channel,” Jim said.

“But this is a book.” Potato flatly stated.

“Yes. And it needs to be about 200 pages to get published.” After a moment he added, “Plus I added one part where they’re watching Jeopardy so it could be a commercial break.”

Potato sighed. “Look, Jim, if you’re committed to this narrative device of having the characters talk out all the financial information you’re trying to convey to your readers, just take one more stab at making this interesting and readable, and we can move on to copy-editing. Have the characters say or do something interesting, or introduce a few more to see how your Rule of 30 works for people in different situations and life stages. I know you can do this!”

Three weeks later, Potato saw that he had a new email from Jim. Subject: I TOOK YOUR ADVICE AND NOW THERE ARE MORE CHARACTERS AND ALSO AN ORGY SCENE

Potato hit reply: “Jim, let’s revert to the previous version of the document and proceed with copyediting. It’s fine. It’s just fine as it was.”

Jim replied immediately: “Thanks so much Potato, your advice helped shape the book for the better for sure. Now I’ll give you some: don’t be so critical in your book reviews. You’re not working as an editor for the author, you’re just giving your thoughts to people at large, and if people think you’re an asshole they’ll be less likely to be nice to your book.”

Potato replied back: “Speaking of which, there was a perfect moment to plug The Value of Simple when the couple needed to know how to invest to capture those returns your actuary character was projecting for them. Why didn’t you?”

Jim’s final reply was BITFD material: “I really want to, it’s truly an excellent guide for the do-it-yourself investor. Really every young Canadian should pick it up, if only so that they know what they’re paying their advisors to do. But my hands are tied here, I’m working with ECW Press and we can’t go slipping in a mention to other books, especially not a self-published work. It’s like that whole conversation about government pensions. My hands are tied, here… Plus if we remind people that other books exist, there’s a danger they might put this one down before they get to the good stuff.”

Ok, I hope that vignette thoroughly demonstrated my point that I did not care for the framework story and how much the extra description slowed down getting to the point, and how very little happened before they had to break and start with a new scene. Plus I can’t imagine anyone will want to go and hire a planner if it takes four months of nearly weekly sessions just to be able to answer the first question in creating a financial plan.

So what about The Rule of 30 itself?

The book is centred on an important topic: how much should you save? From there, it takes off into a discussion of what shape your savings should take: should you aim to save a set percentage of your income for retirement from the time you start work, or should you aim to save more later — you’ll have less time for the magic of compounding to work, but it will be easier to save a higher portion of your income once the costs of childcare and a mortgage are through with.

Fred makes an important point in Chapter 5: “You want your spendable income to be at a tolerable level in all years and to be rising over time in real terms. In fact, I would argue that this should be the second-most important saving goal.” This is in the context of showing that after having kids, or upsizing a house or facing an increase in interest rates on a mortgage, the amount of income available to spend may decrease.

The way to achieve that is the titular “rule of 30”: have the sum of your mortgage, daycare (and other temporary unavoidable costs), and retirement savings be 30% of your income. So when you have high daycare and mortgage expenses, you save less. When your income is higher and your daycare days are behind you, you save much more, ending off with saving 30% of your income in the last few years when your mortgage is paid off.

It’s a neat idea, but I don’t love it. Partly because my own life immediately shows aspects where it doesn’t work. Chapter 7 is on “stress-testing the rule of 30” and mentions some of these factors but doesn’t actually address them to my satisfaction.

What if you get knocked out of the workforce (or off your career trajectory) early, say by untimely disease or caregiving duties? Isn’t back-loading almost all of your retirement savings incredibly reckless? Fred mentions this problem, but just leaves it as a problem: “What I see as a bigger problem is if you are forced to retire much earlier than planned. As with everything else in life, one’s retirement plans do not always pan out. Unplanned early retirement represents one of the biggest challenges to saving for retirement. This is true no matter what rule you follow to save, but it may be a bigger problem with the Rule of 30, since that rule tends to backload your retirement saving.”

What if you’re a renter? Fred suggests that you just use rent in place of the mortgage and carry on. But as housing bulls are so fond of pointing out, rent doesn’t end, so you can’t make the same assumptions about the ability to back-load savings.

What if you live in an expensive city and rent or mortgage is more than 30% of your income? That’s the case for us, and many renters in Toronto pay more than 50% of their salaries on rent. “I can sympathize, but ultimately it means that saving adequately for retirement is going to become more of a challenge.” Yes, and the “rule of 30” will break, but he doesn’t give us a guideline where the rule may or may not apply. I would have preferred some rails on that: e.g., the rule of 30 works great for couples who buy their house by the age of 33 and whose mortgage starts at 33% or less of their pre-tax income, and who will work into their 60’s without getting sick or fired along the way. So anyone living in Toronto or Vancouver should not buy this book, nor anyone who does not have a crystal ball to see the future (or at least who doesn’t have a rock-solid disability insurance policy), nor anyone interested in early retirement.

The last factor that he doesn’t mention influencing the rule of 30 is inflation. Much of the rule of 30 depends on hand-waving wage inflation: your mortgage will be less, or your rent will be less in the future, because your wages will increase faster than your costs, giving you the ability to save more at that time. However, for many in the public service (or other situations) wage inflation running ahead of cost inflation (especially housing cost inflation) is not a given. Here are the salary inflation adjustments for the last 5 years as compared to CPI for an Ontario non-union public-sector employee chosen completely at random out of the sample of convenience we have here at BbtP:

2017: 3%, CPI: 2.1%

2018: 0.86% CPI: 1.7%

2019: 1.6% CPI: 2.2%

2020: 2% CPI: 1%

2021: 2% CPI: 4.7%

Our poor public sector idiots have fallen behind inflation by a cumulative 2.1 percentage points. Ok, but Vettesse wasn’t just talking regular raises that attempt to pace inflation, he also included getting promoted as part of the increased earnings. What if you include that? Including all merit bonuses and seniority promotions for an Ontario public sector employee with consistent top-quartile performance reviews only gets ahead of inflation by a whopping 0.9 percentage points after 5 years — some progress, but not enough to handwave away the assumption that back-loading retirement savings would work out, especially if your mortgage or rent payments are high (he appears to be assuming real gains of 6%/yr in earnings, based on the numbers in figure 7, a figure that I find unfathomable from the flat-as-a-pancake organization I sit in).

Wayfare also works for not-for-profits, and her wage increases (nominal) over the last five years have been:

0%

0%

0%

0%

0%

So you see my problem with the underlying assumptions of the Rule of 30. Yes, Wayfare in particular is perhaps a rare edge case, but I just don’t think the approach to back-loading your retirement savings to the degree the rule of 30 suggests is prudent enough. I don’t think we can safely assume that wage growth will show up as a general feature to make saving easier later, and I don’t think the rule applies as broadly as Vettesse makes it out to be in the stress-testing chapter — at the very least there are not enough warnings or discussions on when it will fail you.

Anyway, my main two issues with The Rule of 30 are that I didn’t care for the narrative framing padding the page count, and that the rule itself didn’t apply to me for at least 3 different reasons.

Beyond that, which is me nit-picking, it was a good book. This is an important question. A vital one: “How much should I save for retirement?” is central to personal finance. And the discussion to get to the rule-of-thumb and some of the considerations are good and important to read.

I like that there is a book that discusses how much you should save, and how much it is a surprisingly hard problem, and takes the whole thing rather seriously, including the trade-offs that saving entails. But I don’t love the replacement of one poor rule of thumb (save 10-15% or whatever) with another, slightly better rule of thumb (mortgage + daycare/some other exceptional costs + savings = 30%) where the limitations are not clearly laid out. I wish that the book had introduced more characters or scenarios to show how the rule works in different cases (rather than just handwaving that it’s robust), and more importantly, showed better where it doesn’t work.

At the very end, he presents an alternative formulation that fits the larger goals of smoothing spendable income over a lifetime that underlie the rule-of-30: “If I could express it differently, I would suggest saving 5 percent of your pay in your thirties, 15 percent in your 40s and 25 percent in your 50s. This alternative represents a rough approximation of the Rule of 30.” I like this alternative much better. Firstly, it sets a floor for saving, so you’re always saving something (even when it’s hard) — that removes the temptation to come up with “extraordinary” expenses that never get you to a point where they’re under 30% so there’s something left to save, and also helps get around the issues where high housing costs may take over 30% of your pay. Saving something early on also makes it more robust to getting kicked out of the workforce early.

Just unfortunate that “the 5/15/25 rule” is not quite as catchy as “the rule of 30”.

And a nice little touch: the book is printed with a two colour process. Really cool to see and props to the graphic designer who used the extra colour well in all the tables, graphs, and chapter titles. It made things pop just that little bit more (and was absolutely necessary for a few of those stacked bargraphs with 6 items).

![]()

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948

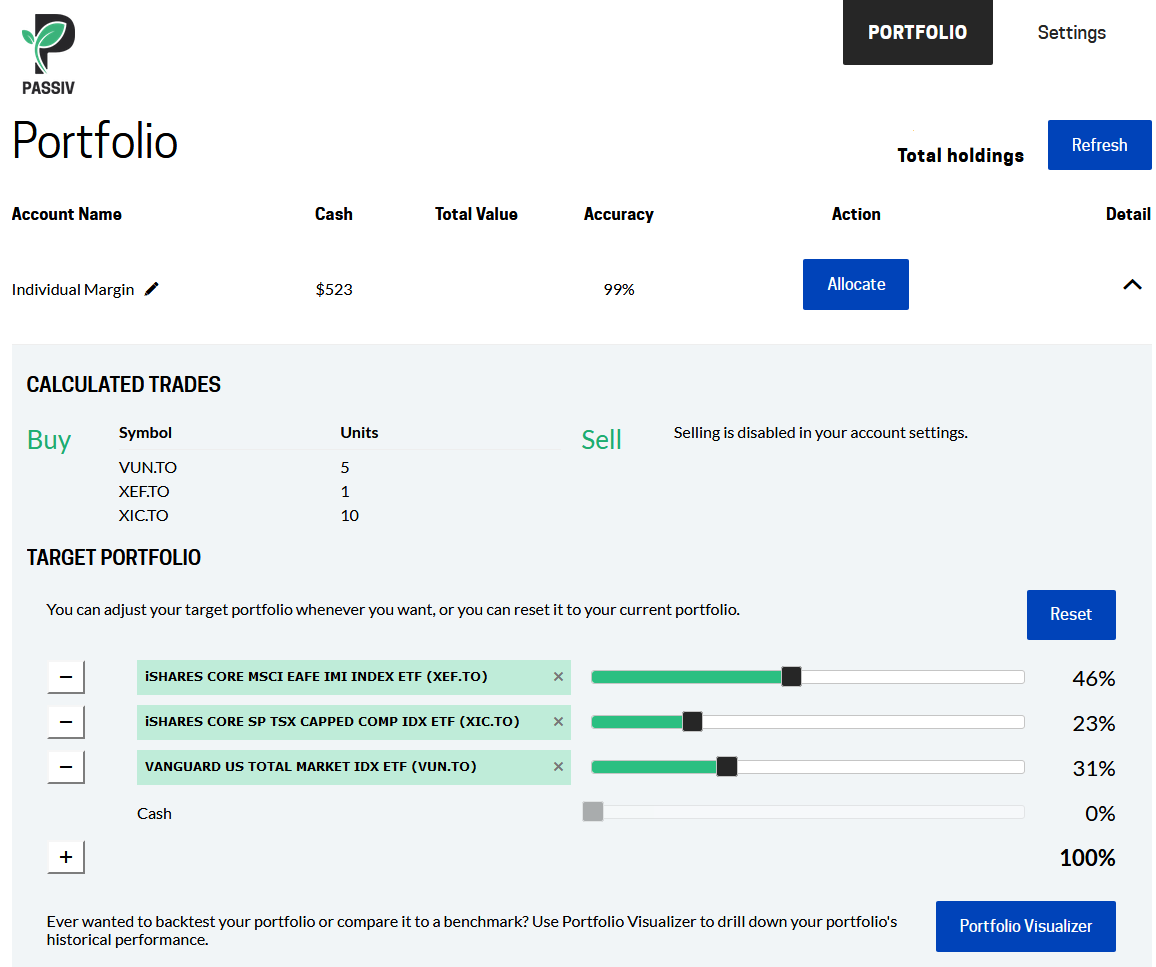

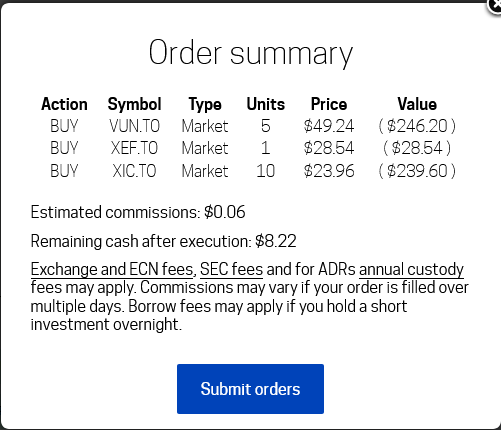

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948 Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.