CPP Calculator Comparison

December 17th, 2020 by PotatoFor a long time I was the only game in town when it came to a CPP calculator that included the CPP enhancements — important for planning purposes! [Note: I’ll point back to the article on the calculator and you can download it from there — if I provide a direct download link here I’ll forget to update it next year and I’ll get hatemail in the future]

Now there’s some alternatives. Doug Runchey (yes, the Doug Runchey who writes all the CPP calculation articles) has teamed up with David Field of Papyrus Planning to create a web-based CPP calculator. It can import data from your statement of contributions if you have that, or you can go ahead and enter data manually. We here at Blessed by the Potato Publishing know that as savvy consumers you have your choice of free-to-use calculators, and there are advantages to choosing Excel: the web-based one will throw an error if you enter earnings that are above the YMPE for each year, forcing you to go back and change. every. line. manually. And fill-down is handy when playing what-if scenarios e.g, for retiring early or re-training. However, some people don’t like spreadsheets (heathens, surely, who wouldn’t read this blog anyway), so it’s handy to have a web-based alternative.

Mine is based on years, while the underlying CPP calculation (and drop-outs) uses months, so I have some approximations there. I also approximate the weird way CPP calculates the maximum pension (based on the average of the last 5 years’ YMPE) to make it easier to use real dollars into the future. That sometimes gives me a few percentage points of difference with other calculators and the ground truth — I tried to future-proof it for estimating far into the future rather than making it more accurate for pensions available today. But there will be some difference — on the main page I put a caveat that it’s only accurate to about 5% (which should be good enough for planning purposes).

So let’s see how the two calculators stack up. I compared 3 scenarios: (all amounts are per year in today’s dollars)

| Scenario | Mine at 65 | DRDF at 65 | Difference | Mine at 70 | DRDF at 70 | Difference |

| 65 yo, max earnings 31-60 | $10,779 | $11,215 | 4.1% | $16,062 | $16,304 | 1.5% |

| 35 yo, max earnings 31-60 | $15,953 | $15,528 | -2.7% | $22,653 | $22,050 | -2.7% |

| 45 yo, 30k/yr 25-65 | $9,585 | $9,380 | -2.1% | $13,610 | $13,362 | -1.8% |

Honestly, I thought the only differences would come from rounding drop-outs to full years and how I estimated inflation for the 5-year average pensionable earnings, and that the differences would likely have come to ~2%, so I was a touch surprised to see a few scenarios with greater differences. Still, all scenarios are within my 5% “good enough for planning purposes” margin of error (assuming that the real value would either be between our two estimates or that DRDF’s version is precise to the dollar). For long-term planning/what-if scenarios you probably have more uncertainty than that about time off work (like in say a pandemic), and if you’re close enough to need precision to the last dollar, then you may want to hire Doug to run a personalized calculation.

It’s also informative to compare the scenarios: the first two are the same set of earnings, just for different starting points. The difference in the amount of CPP the hypothetical people get is due to the CPP enhancements. The 35-year-old has almost their entire working career (since we don’t start them until 30 – 2016) in the enhanced CPP regime, while the 65-year-old finished just as the announcement was being made.

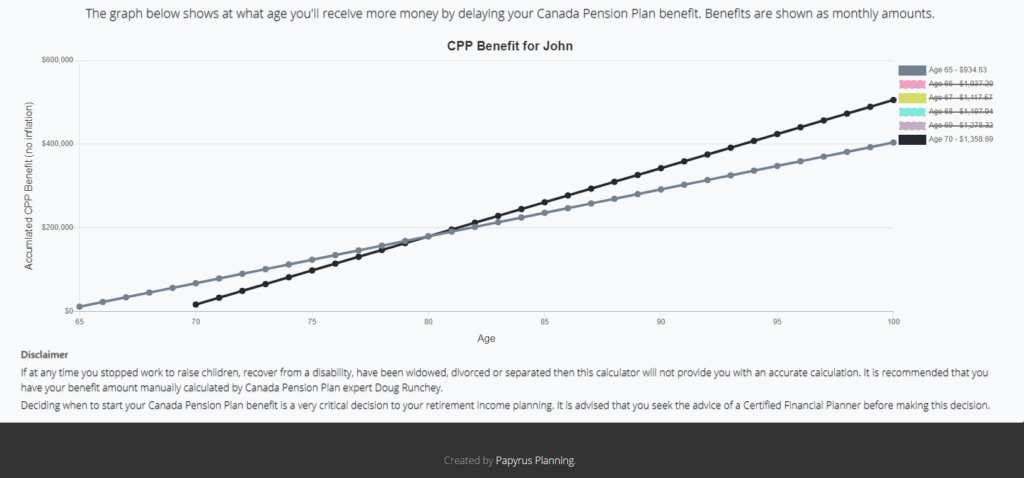

They also include a break-even graph, which is something I’m on the fence about.

I had the idea to add one in to my calculator a few versions ago, but there were two main problems with that: 1) it’s work and I’m short of time and kind of never want to have to dive into CPP calculations again, and 2) I’m afraid it’s terribly misleading. This deserves its own post (which has been in the works for years now and has been scooped (and done better) by MJoM and a recent paper by Bonnie-Jeanne MacDonald) but briefly, it’s a mistake to try to frame it as a decision where you want to get the most out of CPP in an expected value calculation. The point is not to be playing a game of you versus the government* where you die at 75 and go “ha! I took CPP early and WON! Screw you, government!” These break-even analyses frame it wrong and get you thinking about how long you’ll live (which we are really bad at estimating) and make a decision based on that.

CPP has enormous, unmatchable longevity insurance benefits. There, that’s the main point and why you shouldn’t get too hooked into these break-even calculations. Basically, you should always defer it to 70 unless you can’t because you need the money now (i.e., you don’t have the savings to live off of in the first place — which should cover those who would get GIS), or you have a specific diagnosis/severe risk factor that limits your life expectancy (not that your parents died young of something with weak inheritance [like getting hit by a car or having a heart attack] or that you can’t possibly imagine growing that old). Just saved myself another 3,000 word post.

Some people also frame it as spending more early vs later, which is wrong too. As Michael James puts it (though I can’t find the specific post to point to), delaying CPP to 70 lets him safely spend more of his savings now, knowing that the long term is taken care of by CPP — he gets to safely spend more throughout his retirement, including the early years by deferring CPP.

PS: Doug & David say when you sign up that they won’t spam you, and that’s mostly true. They look to have a script set up to send you messages for the 3 days after you sign up, but they’re not solicitations.

* – I have to credit Sandi Martin with coming up with this analogy.

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948 Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.