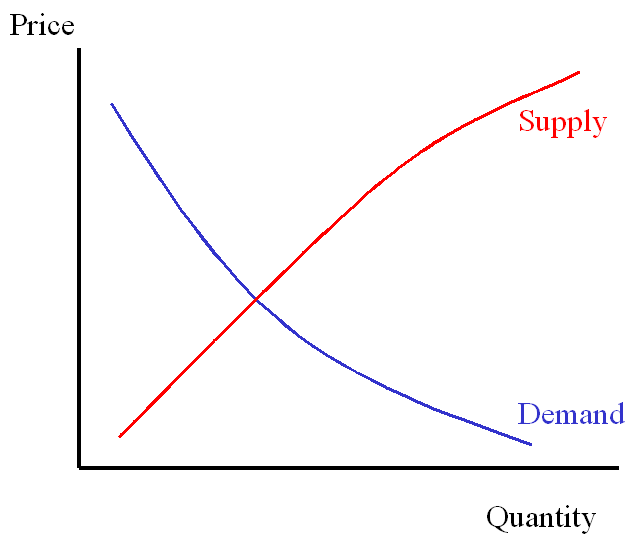

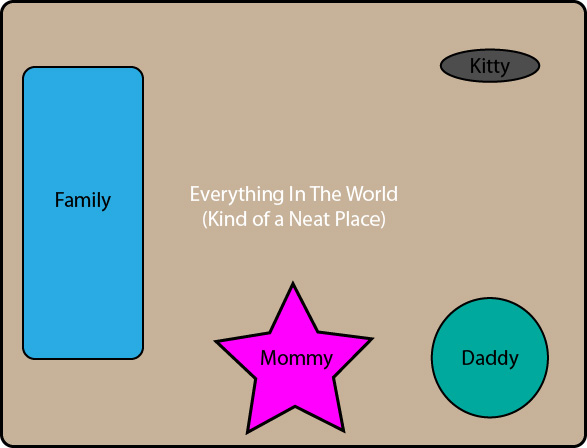

You’ve all heard about “supply and demand†even if only as a back-handed excuse given for why something costs so much. It’s pretty basic economics stuff: even a scientist can follow it. As the price of something goes up, suppliers will be willing to sell more product (and will make changes or substitutions to bring that product to market) while consumers will demand less (and find way to substitute other goods for the expensive ones). Graphically, that looks like:

The shape of the supply and demand curves vary depending on exactly what system you’re talking about, but they have that general property of supply moving up and to the right while demand goes down as you move up in price. (Note that economists usually treat price as the independent variable, and thus have their graphs backwards, but let’s leave that alone – the relationship works either way around). Where the lines meet should be your equilibrium: the same quantity coming to market for both the supply and demand side at a certain price point.

You can then do things to those curves to find what the new equilibrium would be. For instance, if the above graph represents the market for potato chips, we could imagine what might happen in a scenario where say Nelson’s chip truck breaks down. With less supply available, the supply curve would slide to the left, and the price would go up while fewer bags of chips were sold.

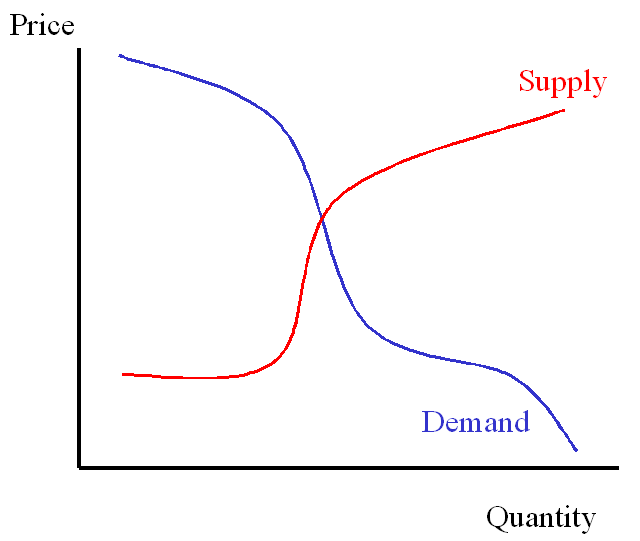

For housing, the demand curve is very flat: most people go through their lives without ever really analyzing the largest purchase they’ll make (and a again, remember the backwards axes of economists – a “flat†curve is actually nearly vertical). They simply get to a point where they figure they can afford it, and they go out and pay whatever the price is to get a house because that is what one does. There are a small number of people at the fringes who can’t afford to buy as prices go up (giving the slight negative slope through the middle), and prices would have to go down a lot before anyone would consider buying a second house. But through most of the range of typical prices, the quantity of demand is pretty stable.

Supply is a little less flat, but still fairly stable compared to many other markets with more substitution options and more responsive supply sources. Above a certain point and you can keep your construction crews operating profitably so away you go. As prices start to get really high supply can start to really ramp up as people get drawn away from other professions to recover supply from the margins (fixer-uppers) or subdivide existing large single units into multiple smaller ones (as seen not only in condos going up over SFHs, but also in Vancouver row houses).

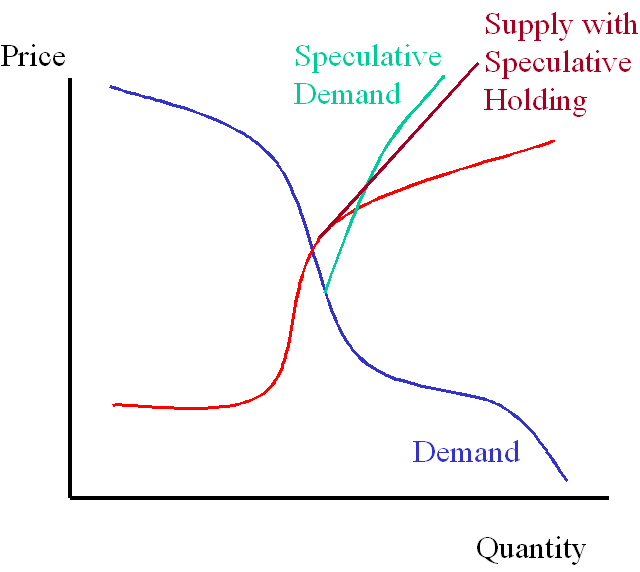

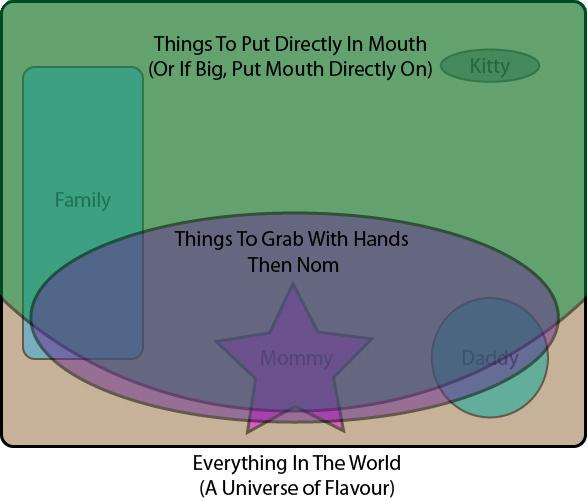

But it’s never this simple in the real world. Supply and demand can be perverse when speculation comes into play. Then you have not just prices versus number of units sold, but also price history as a factor.

If prices were to rise too far too fast, our simple model of supply and demand suggests that more supply should come into play and demand should drop because of the influence of high prices, creating pressure to bring the market back to the equilibrium point. In a mania though, the opposite happens: the price history turns rational buyers and sellers into speculators. Buyers buy more, either borrowing demand from the future in the form of the buyer who’s afraid of being priced out if prices continue to go up, or from speculators buying multiple units with dollar signs in their eyes. Supply is a little more complicated, as it does definitely respond to the higher prices – that’s evidenced in the real-world by the plague of cranes in Toronto and Vancouver slapping together ever taller and smaller condos. But supply also shrinks a bit with strong price history in what’s referred to as “speculative holding†(at least relative to the supply dump we’d otherwise see). With prices on the up-swing, those moving (or moving in together) decide that rather than sell the old place, they’ll hold on to it, sometimes explicitly for investment purposes, but there are anecdotes of those who do it “just in case†even though they would have never considered that holding if price history was less favourable.

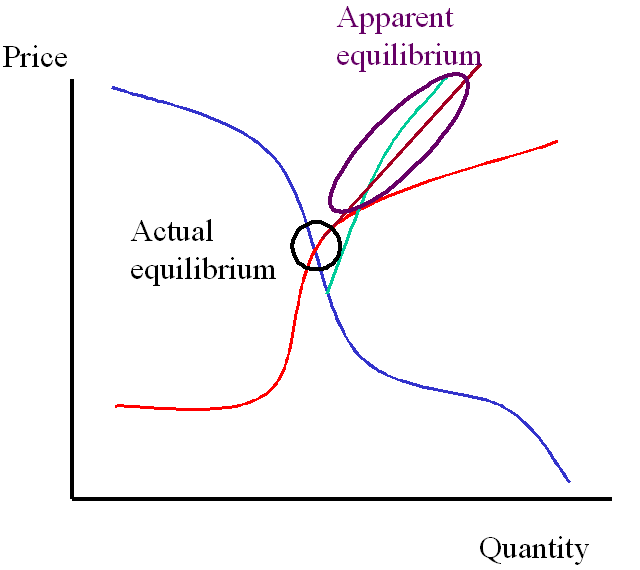

So we see that as prices move up, both supply and demand can increase in proximity to each other, feeding the beast ever upwards (no equilibrium restoring pressures), and the whole time it will superficially appear as though supply and demand are in balance.

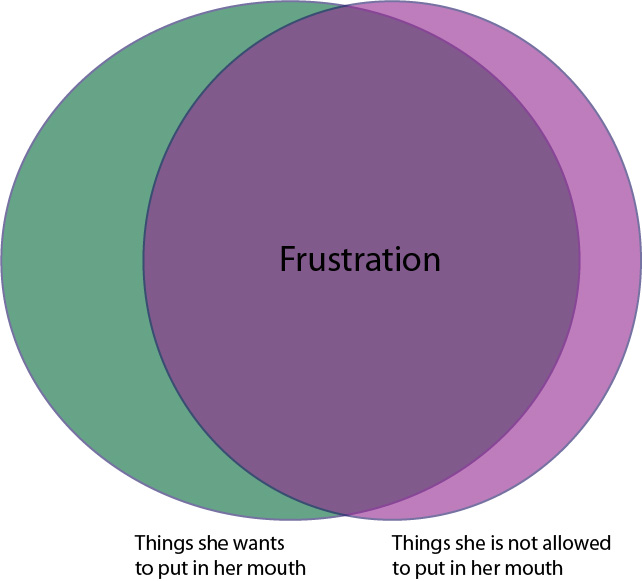

What happens when prices stop rising at a break-neck pace? When they go down a bit – or even just stop increasing – in the so-called soft landing? In a normal market, the lower prices should bring more buyers out of the woodwork to support the new equilibrium. However if it’s not a normal market, but rather one driven by mania and attention to price history, then declining prices are not seen as cheaper but rather a shattering of the speculative world-view. Instead of finding new support for the equilibrium, the speculation in the market dries up. The demand snaps back to the inherent demand curve (which at the high prices, is a lot less quantity) while the same happens to supply (speculative holdings flood the market and listings go up). Supply and demand are – very suddenly! – far apart and there is a lot of pressure for prices to drop back to the original equilibrium.

It is my firm belief that the decline in sales volumes seen in Toronto and Vancouver this summer/fall are the first stages of that.

Now, many are saying that sellers won’t accept lower prices, that they will pull their listings rather than sell at a lower price. This is supported by our conventional view of supply-and-demand, and indeed this is what I expect will happen in the short term. But the speculation also affects the sellers. Those with speculative holdings may no longer be quite so enamoured with the land-lording life (or worse yet, the cash-sucking vacant “just in case†condo), so they may sell a bit below the peak (though the early ones will walk away with personal profits). As price momentum turns negative, the thoughts of holding out for better days turn to fear that negative price movements will persist, and panic sets in. Meanwhile, the builders who pulled out all the stops to meet the crazy demand of last year can’t stop on a dime.

There are many pundits out there with a basic understanding of “supply and demand†and who try to change their vision of the real world to fit that – in other words, they play up evidence that demand is legitimate (whether from immigration or a secular shift in how much of their paycheque the average Canadian is willing to put towards housing expenses) in order to explain high prices. But that simple model doesn’t really leave room for bubbles, manias, and speculation. Of course, I might be wrong – I still have to stop and think about those damned backwards axes every time – but at least the mental model I’m working from has the possibility of generating a bubble. For some bulls, they don’t think there’s a bubble not because of the weight of evidence, but because an overly simplistic model of supply and demand simply doesn’t allow for the possibility.

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948

Questrade: use QPass 356624159378948 Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.

Passiv is a tool that can connect to your Questrade account and make it easier to track and rebalance your portfolio, including the ability to make one-click trades.